A defining quality of student-centred teaching is effective assessments. In recent years, the discourse around effective assessment has steered towards incorporating the “assessment for learning” strategy into curriculum development. In basic form, assessment for learning entails assessment where pre-emptive, future-oriented comments (called feedforward) are given to learners to guide improvement in future performances. This contrasts with the typical assessment arrangement where feedback is considered a product offered to the student in exchange for what they submit. However, two broad factors have historically impeded the adoption of assessment for learning with feedforward corrective actions in educational settings:

- Increased workload and scalability: This approach demands creating varied, low-stakes formative assessment tasks with actionable feedforward recommendations that guide future learning. Besides, providing personalized corrective actions for each student in each low-stake test is both time and resource-intensive. Particularly, in large courses with many students, the additional burden on educators’ heavy workloads cannot be underestimated.

- Student engagement and motivation: Students are reluctant to engage with formative assessment tasks if they perceive them as low-stakes with no incentive that aids their grades.

Overcoming these impediments is crucial to accelerating progress with assessment for learning. In this vein, the central idea of the assessment flywheel is to harness the power of GenAI to overcome the above challenges. In effect, this approach adds to the growing realisation of the power of GenAI for the transformation of assessments.

The Assessment Flywheel Model

Why assessment flywheel? In the field of engineering, which is my academic background, traditional methods such as lectures, tutorials, and laboratory sessions are the dominant content delivery vehicles. However, oftentimes, these activities are lecturer-led and time-bound. This thus limits students’ active knowledge consumption and self-regulated learning. Compounding the problem further when it comes time to assess our students’ learning, lecturers tend to focus predominantly on summative assessments, which are often followed by feedback of one kind or another. Notably, this prevalent approach of provisioning meaningful feedback solely on summative assessments often creates a dilemma between the traditional assessment of learning (which is backwards-looking) and the assessment for learning (which is forward-looking).

The discourse around how to incorporate assessment for learning strategy into curriculum development has permeated the literature on teaching and learning for the past several years. However, progress has been slow in adoption. Among the reasons for this is that assessment for learning demands constructing and assessing a diversity of low-stake formative assessment tasks suitable for providing “feedforward” comments that trigger corrective actions in students. In other words, the new paradigm imposes a significant burden on resource-constraint educators, especially for a large cohort of students. And this is where the idea of “assessment flywheel” comes in.

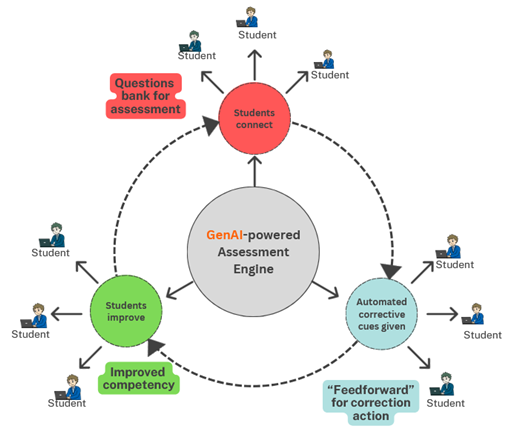

Essentially, the assessment flywheel is a GenAI-mediated assessment framework. It is a dynamic, self-reinforcing system that continuously gathers, analyzes, and applies student performance data to enhance learning outcomes. As depicted in the figure below, the flywheel model operates in a continuous cycle, and each iteration of tasks, learning and proactive feedforward comment builds momentum for deeper skill development. This contrasts with the traditional assessments that are static and episodic. More specifically, within the flywheel model, the GenAI plays a central role in generating personalized tasks, personalized feedback, and adapting learning materials. The goal is to create an automated loop where student learning accelerates over time through persistent, data-driven refinement. The model allows instructors to incorporate personalized exercises that revolve around a subject’s learning outcomes in low-stake tests. And with proper tailoring of the assessment flywheel model for low-stake tests, students will be able to instantly identify their current state of progress and get instant comments for corrective action from the GenAI-powered system.

An illustration of the assessment flywheel towards achieving the idea of “assessment for learning” using LLM/GenAI (adapted from the author’s recent publication).

Rolling Out GenAI-Driven Assessment Flywheel to Improve Learning

To be effective, one will need to take a few steps before a GenAI-driven assessment flywheel can be introduced within the academic learning spaces. First, the “assessment flywheel” system will need to be fed with learning contents of specific subjects from which question-answer pairs can be automatically generated. With proper tailoring of such a tool for low-stake tests, students will be able to instantly identify their current state of progress and get instant comments for corrective “feedforward” action from the GenAI-powered system. Second, a mechanism to minimize hallucinations (a common problem with GenAI) must be in place. Third, a structured approach that guides users of the system will need to be instituted with the rollout. For this latter point, a framework similar to Professor Gilly Salmon’s five-stage model for online learning is recommended.

Conclusion

Overall, GenAI holds concrete pedagogical prospects as a way of augmenting traditional teaching and assessment approaches to enhance gains in students’ learning. The discussed GenAI-powered assessment flywheel embodies the spirit of the military strategy of “Observe, Orient, Decide and Act” or OODA as is well-known. In the context of a personalized learning strategy, this GenAI-powered assessment flywheel approach holds the potential to contribute to deepening students’ accomplishment in competencies associated with learning objectives. It will also allow educators to provide assessments that facilitate authentic learning with minimal addition to their workload.

Dr. Khameel Mustapha holds a PhD in mechanical engineering from Nanyang Technological University (Singapore). He also holds two teaching qualifications – Postgraduate Certificate in Higher Education (PGCHE, Nottingham UK) and Graduate Certificate in Teaching and Learning (GCLT, Swinburne Australia). He is currently an Associate Professor with the Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Nottingham (Malaysia campus). He is a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (UK).