Students need to demonstrate their competencies in areas beyond traditional classroom assessments. In an era of advanced technologies and artificial intelligence, the use of these tools in education raises concerns about its impact on student learning, particularly when it comes to assessments. When completing assignments or preparing for tests, there is a concern that they might be “faking it until they make it.” This means that instead of genuinely understanding the material, students may simply perform well on assessments because they have access to AI tools that help them produce correct answers without deeply learning the concepts. We argue that educators need to strive to provide more authentic learning experiences that do not easily lend themselves to the use of advanced technologies. One way to do this is by providing experiential learning opportunities for students to demonstrate their competencies in a more real-world setting. This can be revealing for educators as they see a different side to students exploring and applying course content in authentic ways. The purpose of this article is to provide considerations for educators when creating experiential learning opportunities for students. Although the ideas presented in this article stem from a continuous topic of exploration in higher education, (see Beard & Wilson, 2006; Cantor, 1995; Finely & Bowen, 2021; Tormey, 2022 for further research), this article summarizes our learning and interpretations when creating experiential learning opportunities for our students.

Consideration 1: Examine Your Course

The first consideration in creating an experiential learning opportunity is to review the student learning outcomes (SLOs) for your course, paying special attention to the outcomes that are difficult to assess with traditional methods. Consider which outcomes students often struggle to meet, express frustration over, or where you feel the current assessments do not fully capture their performance. Reflect on whether there are students who perform well on assessments, but based on their actions in class, you have concerns about how they would perform in real-world scenarios. For instance, is there a quiet student who excels in written assignments but struggles with a course outcome tied to public speaking? Next, consider the content students need to master, the depth of their understanding, and the skills they need to apply that knowledge in practical situations.

Consideration 2: Identify the Learning Experience

After reflecting on your course design, the second consideration is to identify the type of experience you want students to engage in that can help bridge the gap between theory and practice and determine how you will assess their success. These real-world experiences should enable students to engage more deeply with course content while providing you with an opportunity to assess their performance in a more authentic manner. Thus, it is essential that you identify the objectives for the learning experience. For example, you could assign students to work with local businesses or startups to develop a marketing plan or facilitate a lab project where students work with local environmental organizations to analyze water quality or air pollution. This would allow them to apply specific concepts and theories, such as market segmentation, financial forecasting, or chemical testing techniques in a real-world context. In terms of assessment, consider using a combination of observation, reflective journaling, and authentic application of skills. For example, education students might learn a literacy strategy in class and then apply it in a real teaching context, with the reflective journal capturing their thoughts on the effectiveness of the strategy and the challenges they encountered. This approach allows you to assess not just what students know, but how they apply their knowledge in real-world situations within a supportive learning environment.

Consideration 3: Seek Collaborative Partners

The third consideration is who to partner with. Collaborative partners can include community agencies, businesses, government institutions, public institutions, and even on-campus collaborators, such as university entities. The goal is to involve the right stakeholders—those who are decision-makers or have the influence needed to make the collaboration meaningful. Following Covey (2013) principle of “Think Win-Win” from his 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, partnerships should be approached with the mindset of creating mutually beneficial outcomes where all parties succeed together. Successful collaborations are built on shared goals, complementary strengths, and clear communication. Covey’s (2013) “Seek First to Understand, Then to Be Understood” emphasizes the importance of understanding the needs and priorities of your partners before asserting your own. This mindset fosters deeper, more empathetic connections, ensuring that both sides are fully aligned in the objectives of the experiential learning. To build an effective partnership, it’s crucial to establish a win-win foundation, where each partner feels their contribution is valued and that they are gaining something meaningful from the collaboration. Covey’s (2013) habit “Synergize” focuses on leveraging the strengths of each party to create something greater than the sum of its parts. By combining the unique talents, resources, and perspectives of each partner, you can foster a powerful, cooperative environment.

Consideration 4: Create a Timeline and Execute

The fourth consideration is establishing a realistic timeline that includes the planning, implementation, and assessment of the experience. Planning the experience should be intentional and will take time; therefore, it is recommended that the process is started at least one semester prior to implementation. Additionally, clearly identifying and articulating the roles and responsibilities of each partner is vital. Each partner should understand their role in the collaboration, what they are accountable for, and how their contributions will benefit both themselves and the partnership as a whole. For example, if a literacy course is partnered with a local school district to offer an afterschool program to youth, the school district may assume responsibility for recruiting youth to participate whereas the teacher candidates would provide the literacy instruction. This clarity, along with open lines of communication during implementation, ensures the longevity and success of the partnership. At the conclusion of the semester, assessment must be conducted to evaluate the overall experience from each partner’s perspective. Partners need to meet to review next steps and discuss areas for program improvement. A debriefing meeting should be held within a few weeks of ending the experience in order to make necessary adjustments before a new implementation cycle.

Consideration 5: Experiential Evaluation

The fifth consideration is to determine how you will evaluate the success of the experience. Schon (1983) identifies two types of reflection: reflection in action and reflection on action. Reflection in action refers to observing, contemplating, and responding to events that occur during the experience allowing individuals to adapt and address challenges in real time. For example, an accounting course has partnered with an organization to assist community members with tax filing and has discovered that individuals have limited English proficiency. Through in action reflection, partners can quickly respond by arranging language support and ensure the tax assistance continues smoothly. Furthermore, reflection on action requires gathering feedback from partners through surveys, anecdotal records, and discussion after the experience to inform program improvement. Referring to the accounting class example, all involved participants should be asked to reflect on the experience. Their feedback can then be analyzed during a debriefing meeting to evaluate the program and identify necessary changes for ongoing implementation.

Consideration 6: Refine for Future Progress

The final consideration is to refine the experience to ensure continuous improvement and future growth. Data collected from assessments and evaluations should be analyzed to identify strengths, areas for improvement, and insights that inform decisions about future iterations of the experience. Faculty must consider the learning experience, specifically how it is aligned to the course and if students met the SLOs with success. Likewise, partners need to consider the sustainability of their involvement for ongoing implementation. This reflection process is essential for making adjustments that enhance both student outcomes and the partnership moving forward.

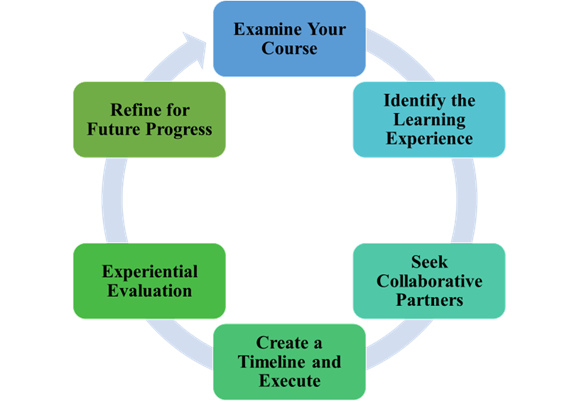

Figure 1

Consideration Cycle

Conclusion

These considerations have emerged from personal experiences developing experiential learning opportunities for students. We strongly encourage faculty to incorporate more authentic learning opportunities into their course design as a means to combat challenges posed by advanced technologies. Partnerships have the power to provide students real-world learning that fosters deeper understanding and academic excellence.

Elizabeth Falzone, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of education at Niagara University.

Karen Poland, Ed.D., is an assistant professor of education at Niagara University.

References

Beard, C., & Wilson, J. P. (2006). Experiential learning: A best practice handbook for educators and trainers (2nd ed.). Kogan Page.

Cantor, J. A. (1995). Experiential learning in higher education: Linking classroom and community (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 7). ERIC Clearinghouse on Higher Education, Graduate School of Education and Human Development, The George Washington University.

Covey, S. R. (2013). The 7 habits of highly effective people: Powerful lessons in personal change. Simon & Schuster.

Finley, L. L., & Bowen, G. A. (2021). Experiential learning in higher education : issues, ideas, and challenges for promoting peace and justice. Information Age Publishing, Inc.

Schon, D. A. (1983) The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

Tormey, R., Isaac, S. R., Hardebolle, C., & Le Duc, I. (2022). Facilitating experiential learning in higher education: Teaching and supervising in labs, fieldwork, studios and projects. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781003107606