In my (re)reading of Parker Palmer’s The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life (1997) and its iterations, it becomes more obvious to me that Parker is a paradox savant.

“What makes a Rosa Parks?…What makes a Nelson Mandela? What makes these people is their capacity to take the inner life seriously, and to tap the sources of power that lie within, that are just as essential as external forces in transforming our institutions and society for the better” (Parker Palmer, 2015).

In the work that educators do each day, how do we speak up and take action for what’s right in higher education? For Palmer, the answer lies in our interior and outer landscapes that are complementary opposite. That is, while there is an interplay between the two, it is the inner life, our identity, and integrity that propels us to find our voice, elevate good ideas, and call out organizational barriers that impede shared goals.

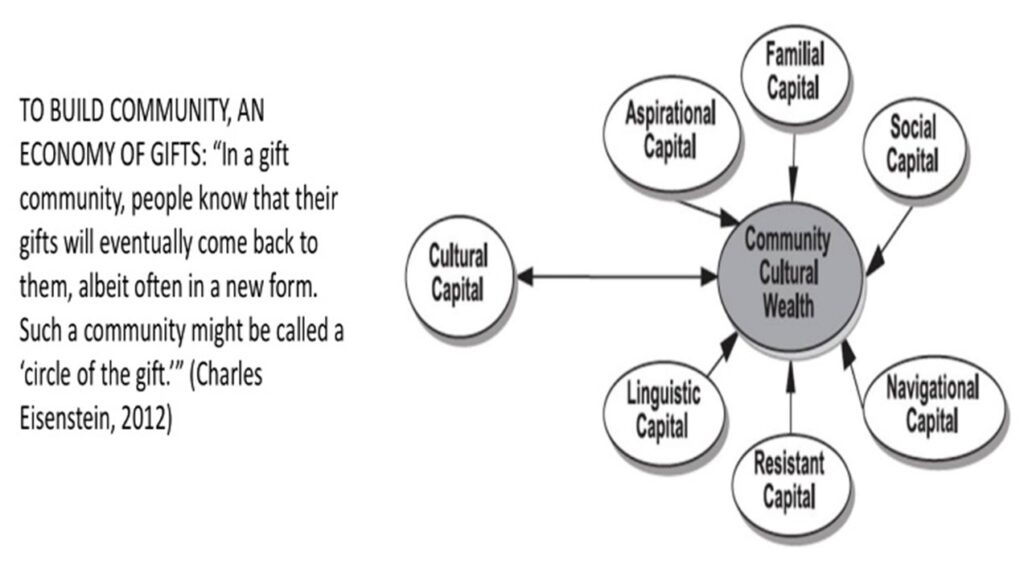

By examining teacher education, professional education, and management education, we find common objectives aimed at fostering human potential amidst the simultaneous fragmentation and integration of our world. However, drawing from The Courage to Teach, it seems to me that all of these disciplines share a common problem: they focus on developing externally oriented knowledge and skills so that our world (and our students) can adjust and refocus on human aspirations.

Thus, some educators promote human flourishing by focusing on external activities—adopting new pedagogy techniques, new technology, and changing the curriculum. While these external influences can facilitate the development of a curriculum inspired by human flourishing, they also carry the risk of resulting in a superficial framework. This type of curriculum can promote a tick-box culture which has little buy-in from faculty, staff, and students to actually bring about substantive changes.

Certainly, as Palmer suggests, a key factor contributing to this superficiality is the tendency for leaders to ascend to their roles by demonstrating exceptional competency and efficiency in the external world. This phenomenon often arises from the inherent inclination of individuals who attain leadership positions and may suppress their inner awareness, fearing that it may expose their imposter syndrome and associated vulnerabilities. As such, there is a “broken paradox” in organizational settings where leaders rely on their outer work without needing the inner work to acknowledge personal contradictions—inner work that leads to changes in behavior and inner work to deploy skills with purpose.

“It’s easier to deal with the external world. It’s easier to spend your life manipulating an institution than it is dealing with your own soul. It truly is. We make institutions sound complicated and hard and rigorous, but they are a piece of cake compared with our inner workings!” Parker Palmer (1999, p. 82)

For example, the diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiative in higher education can serve as an appealing framework. However, the challenge lies in establishing a campus culture and structure that genuinely prioritizes racial and gender equity. The answers provided by current leaders often seem to revert back on how they can be more vocal and transparent about what DEI means and how every individual can practice and build it through best practices. Of course, seldom do the best practices include the need to exercise and strengthen our inner work.

For Palmer, when you begin to work on your inner life, you become aware of a “tragic gap” between your integrity and the way your university operates. “And you may become aware that you are part of the problem—that you live a divided life, that the actions your institutions demand of you conflict with your inner values.”

Share your “courage to teach” with your students

Because the inner life can potentially disrupt norms, it requires us to develop the skills and aptitude for introspection and to embark on an inner exploration. This journey enables us to comprehensively grasp our instincts, which may both support and challenge aspects of DEI.

For me, when educators encourage formation and transformation among students, there is likely an implicit pushback from students, especially if they can’t explicitly see the effort their professors have put into their own inner work. If educators skim on their inner work, their outer work may look superficial and may not be taken seriously by students. This could negate “relational trust” in the classroom which is an important link to students’ performance and growth.

As educators come to realize that their inner and outer work complement each other rather than contradict each other, they’ll also recognize the potential for inner growth and external action to harmonize, leading to a deeper foundation from which to advocate for authentic social change. By taking such actions, it’s probably that our students—a majority of whom indicated in a 2023 survey that they would contemplate transferring if their college were to discontinue DEI initiatives—may follow suit.

Recently, my courage to teach has led me to share with colleagues and students of how my “second father,” Maurice Pritchett, who was an African American middle school principal for 30 years who passed away a year ago, has profoundly shaped my life. Through this, I’ve reflected on the complexities of my own family’s journey when we cam to the US as boat refugees in the early 1980s. While my sharing encompasses various facets, its overarching aim is to share a more personal and humanistic dimension of DEI.

Where in your life have you witnessed a profound positive influence of a single person?

Now, when I teach my business course on social justice and experiential learning, I have more conversations throughout the course about how my personal and professional experiences have led me to create this course. I am transparent when discussing why I assign students to “teach-to-others” in marginalized middle and high schools on financial literacy and financial capability. Moreover, I share with students my rollercoaster in terms of my personal and professional formation and transformation.

In context for educators to be an agent of social change for the outer world, Palmer’s concept of “we are who we teach” requires us to have the courage to delve courageously into our inner identities. Otherwise, our inability to embrace and manage our personal contradictions will surface, and our commitment to social change becomes “performative theater” at best.

Long Le is a faculty and director at the Leavey School of Business at Santa Clara University. He has a blog at GlobalCitizenBiz and he runs a zero-interest microfinance with his students.

References

Palmer, P. (1998). The Courage to Teach : Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life. San Francisco, CA :Jossey-Bass.