Connecting with students is one of the most rewarding aspects of a professor’s job. Some faculty hesitate to teach online, frequently offering the rationale: “I want to connect with my students. There’s just not enough interaction and engagement online!” Faculty are not alone in yearning for this connection – students want it too!

Frustrated by the lack of real-time exchanges with students, I incorporated live or synchronous sessions into my online classes a few years ago. I experimented with the latest tools and made adjustments each semester based on feedback from students. To my surprise, students consistently requested more synchronous engagement. After doing so, I gained a new appreciation for the potential of creating meaningful connection virtually.

When many universities rushed to provide remote instruction due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I leaned on my synchronous experience to train faculty on the pedagogical potential of platforms like Zoom. Training amidst this crisis gave me insights on what instructors new to synchronous teaching struggled with the most. In this article, I share these insights and provide four strategies for optimizing the student experience in synchronous sessions.

#1. Plan and Organize Thoughtfully

Organization and course design are especially important in online environments. In designing your synchronous sessions, think through the pedagogical value of each component, placing your students’ learning and experience at the heart of your plan.

Part of being student-centered is recognizing their limited attention spans and planning accordingly. Gavett (2014) notes that many employees spend their virtual meetings doing other work, cooking, eating, or Amazon shopping. Online students are now multitasking more than ever, balancing the extra demands on their time. Running long sessions, especially past 60-90 minutes, increases the likelihood of competing distractions. Carefully review your game plan before each session and create a minute-by-minute schedule. Sharing an outline at the start helps students follow along and you can save valuable time by opening all files you will need ahead of time.

Being efficient requires the instructor to recognize asynchronous portions as complements to live engagement. Ask yourself, “Can I accomplish the same goal asynchronously?” For example, student introductions can be time-consuming in a larger synchronous class. Instead, have students use a Discussion Board or a video-based platform such as FlipGrid. For largely one-way communication, record a video and ask students to watch it before/after class.

#2. Clarify Purpose, Norms, and Expectations

While synchronous sessions may be new to some instructors, oftentimes students are also unfamiliar with this format. Even if they participated in synchronous sessions before, those experiences may vary greatly. Laying the foundations of why and how you conduct your class helps set expectations, creating a shared class culture where students take more responsibility for their participation.

Record a video before your first live session explaining the purpose (“How will these sessions contribute to student learning and growth”), any equipment they will need (e.g., camera/mic), and your expectations of engagement. Clarify aspects such as, “Are these sessions required or optional? How does this fit into my grade? Is there an asynchronous alternative if I cannot join?”

Establishing an expectation of cameras turned on can greatly enrich the experience for students and instructor. For students, cameras create a focused learning environment with less distraction – one much better than “dialing-in from the road.” Video also helps the instructor know when students are lost, bored, or at least that they’re still present!

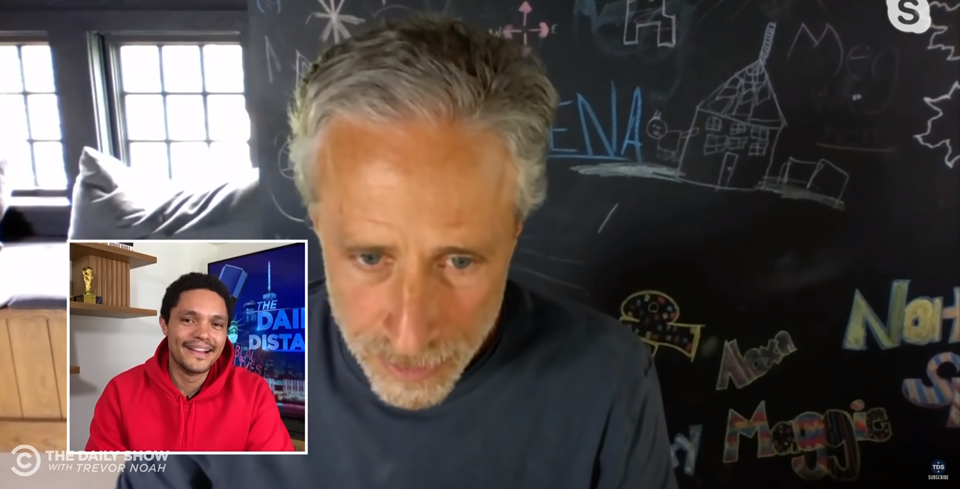

Instructors should model for students an effective virtual presence. Ensure the lighting in your environment allows students to see you clearly. Stay in the center of the frame and look into the camera when speaking (Don’t worry, even Comedian Jon Stewart had to be reminded by The Daily Show host Trevor Noah on how to do this correctly).

Consider investing in an HD webcam, headset, or an external mic (e.g., Blue Yeti). While these may seem like luxuries, being able to see and hear the instructor well greatly enhances the student experience.

#3. Build Community through Faculty-Student and Student-Student Interaction

Social check-ins create community. If I only turn on my camera and audio right at the start of class, that would be similar to walking in the door of my in-person class right at the scheduled start time and going straight into teaching. Whether in-person or online, those precious minutes before and after class are critical for answering questions and connecting with students. Login several minutes before class and greet students as they come in. Consider starting with fun virtual exercises.

Synchronous technologies have evolved considerably from text-based chat rooms common in the 90’s. In Zoom, breakout rooms can be used to create student-student interaction for think-pair-share or team-based exercises. Just make sure directions are extra clear before you send them to their virtual rooms and post in your Learning Management System (LMS) beforehand any worksheets or instructions they will need. Zoom even allows you to float the room, checking-in on groups as they work. Students are often most surprised by breakout rooms – they never expected live interaction with their peers in online learning!

#4. Use Technology but Be Careful of Going Overboard

Today’s platforms are equipped with so many engagement tools it can feel overwhelming, even for students. I suggest starting with polling as a relatively easy to use option, especially since instructors may already use them in the classroom. Polling can be an effective way to engage students with practice exam questions, ice breakers, or general pulse checks (“Rate your understanding of this concept”). Build polling into your game plan as warm-ups or transitions between activities. Polling can also be used to create student-centered discussion similar to the use of Clickers.

Accessibility is often a challenge in online courses. Thankfully, a number of tools have made accessibility easier. When using cloud recording, Zoom auto-captions the session enabling students to watch a closed-captioned recording after class. If using GoogleSlides, students can see live captioning during class.

In sum, when it comes to technology, take a gradual approach. Sometimes, when faculty learn about all the tools available, in our zeal to create the best possible experience for students, we run the risk of trying to do too much. Avoid jumping headfirst into the bells and whistles, giving yourself time to grow incrementally. As you gain more experience, you’ll learn which tools best fit with your teaching style and pedagogical strategy.

The COVID-19 pandemic has many of us teaching in unfamiliar situations. Perhaps a silver lining has been the widespread practice of synchronous instruction, a potential remedy for the connection students and faculty often miss in traditional online classes. The exponential growth of synchronous sessions will likely shape a “new normal” for online learning, long after the pandemic has passed.

Zahir I. Latheef is an assistant professor of management at the University of Houston-Downtown teaching courses on leadership, teams, and nonprofits. Once a skeptic of online learning, Zahir is now an OLC Advanced Certified Instructor and regularly provides training and coaching for faculty on synchronous instruction.

References

Gavett, G. (2014). What people Are Really Doing When They’re on a Conference Call. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2014/08/what-people-are-really-doing-when-theyre-on-a-conference-call

Hakala, C. (2015). Why can’t students just pay attention? Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/effective-teaching-strategies/why-cant-students-just-pay-attention/

Lorenzetti, J.P. (2014). Four crucial factors in high-quality distance courses. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/online-education/four-crucial-factors-high-quality-distance-learning-courses/

Madjidi, F., Hughes, H. W., Johnson, R. N., & Cary, K. (1999). Virtual learning environments. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED429565.pdf

Martin, F. & Bolliger, D.U. (2018). Engagement matters: Student perceptions on the importance of engagement strategies in the online learning environment. Online Learning, 22(1), 205222. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1179659.pdf

Moore, E.A. (2014). Improve accessibility in tomorrow’s online courses by leveraging yesterday’s techniques. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/online-education/improve-accessibility-tomorrows-online-courses-leveraging-yesterdays-techniques/

Santhanam, S.P. (2020). A reflection on the sudden transition: Ideas to make Your synchronous online classes more fun. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/online-education/ideas-to-make-your-synchronous-online-classes-more-fun/

Shepard, L. (2012). Using student clickers to foster in-class debate. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/effective-teaching-strategies/using-student-clickers-to-foster-in-class-debate/

St. Amour, Madeline. (2020). A double whammy for students. Inside HigherEd. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/03/31/student-parents-are-hit-doubly-hard-coronavirus

Udermann, B. (2019). Seven things to consider before developing your online course. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/online-education/seven-things-to-consider-before-developing-your-online-course/

Wehler, M. (2018). Five ways to build community in online classrooms. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/online-education/five-ways-to-build-community-in-online-classrooms/