One of the wonders of teaching is the chance to be an active explorer: we get to experiment, take risks, and try new things. With the abrupt shift to online teaching, 2020 was a great exploration year.

As I reflect on 2020 and plan for 2021, I can’t help but be reminded of my weekly get-togethers with my colleagues, virtually and sometimes in person, socially distancing in our backyards. With no structure for our gatherings or preconceived ideas of how it should be, yet with our shared disciplinary knowledge, we talked freely about what mattered to us: effective teaching. Some of our conversations explored the digital divide, but others centered on how to start and sustain teaching through a pandemic, which encouraged me to revisit a paper I had read on emotional presence.

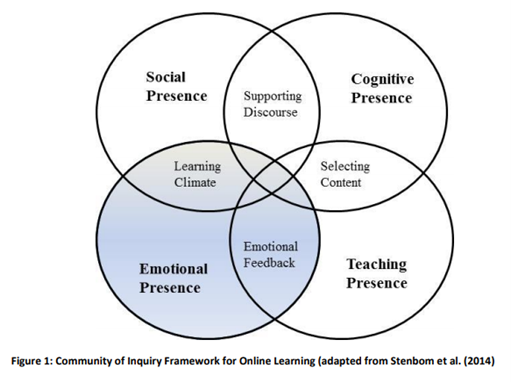

Emotional presence is an addition to the original, well-researched Community of Inquiry Framework commonly used for online teaching and learning (see visual below), according to research analytics Rienties and Rivers (2014) in their review study. They concluded that emotional presence is a key driver to online learning; particularly, how students feel has an impact on their motivation, self-regulation, and academic success (Rienties and Rivers, 2014).

As I reflect on this study, I also thought about the feelings of isolation during this pandemic. Maybe you have too. I wondered how students in my class were processing it. Since social interactions can easily get lost in remote instruction without thoughtful planning, I applied the concept of emotional presence and its overlapping counterparts to position student engagement at the forefront of my online course. To do this, I implement book groups.

Book groups

To get through 2020, a “tough year” complicated by isolation, anxiety, grief, and fear, I agree with literary critic Maureen Corrigan that books have the power to connect: “Books break through. They enter directly into our heads, occasionally our hearts.” Especially when reading a shared book, the act of communal reading gets us to think, feel, and talk. Reading is emotional when books affirm our challenges, disrupt our identities, or foster empathy; it is social when we engage our voice and respond to other readers; it is intellectual when we dissect the author’s rhetorical techniques or analyze how issues presented in books play out in society. One page at a time, a well-chosen book can touch on these aspects of engagement, highlighting the value of book groups.

With our online education locked in Zoom boxes, having conversations in book groups can serve as an outlet for pandemic isolation. When students draw from their experiences and backgrounds to engage in conversations about a shared book, the outcome is self-reflection and discovery. For example, in my first-year writing class, one of my book groups chose to read Dear America by Jose Vargas, a graduate of San Francisco State University, where I teach. While this book is a personal story of how the author kept his immigration status hidden, it also examines racial issues in the U.S. immigration policy: who gets in, who’s barred, and who gets to be a citizen. But what unfolds is how so many students in my class critiqued the author through a personal, human lens. They brought up abandonment issues and how feelings of betrayal can lead us to be suspicious of others, making us feel different or odd. Others commented that we become emotionally complicated when we miss the developmental stages of our teenage years or lose parental trust. “We are broken when we come from broken places,” is how one student puts it. Naturally, when students open up to share what they think and feel, we catch a glimpse of their scars. While we can’t unpack it and do the work of a therapist, we could validate sensitive issues of trauma by showing empathy or offering emotional feedback, through which we acknowledge, recognize, and respond to the emotional state of others. These give-and-take conversations improve our emotional state and help us feel connected in a socially-disconnected time.

Tips for designing a book group

To design a book group, consider goals, pedagogy, and disciplinary practice. My goal is to incorporate conversations, tapping our voice, emotions, and intellect to ease social isolation. I draw on my teacher training, on the importance of human presence and interactions as ingredients for learning, supported by a recent working paper on the benefits of peer interaction during the pandemic. I also draw from my discipline, composition studies, which has a rich teaching history focusing on post-secondary writing. Thus, my book groups are designed to support these principles. The process includes the following:

- Student choice in book selection: Students in my class choose a book from a list of three: Born a Crime by Trevor Noah, Educated by Tara Westover, and Dear America by Jose Vargas. No matter what discipline one teaches, choosing books that explore cultural identities and display real-life issues will empower students to engage.

- Student choice in writing prompts: Once students have chosen a book and begin reading, they write three weekly short papers, choosing from six different prompts (e.g. author’s arguments, author’s rhetorical strategies, key issues, areas of reading difficulty, questions raised, and character analysis). Each week, we workshop one of these papers to discuss writing strategies: choices a writer can make, what’s working well, and what can be improved. These conversations, in turn, help foster a classroom community.

- Student-led discussion groups: While students write for homework, they discuss their shared book in small groups (6-8 students) during in-class meetings where one day of the week is reserved for book discussions. Generally, three small groups meet for 25 minutes, each back-to-back, with the faculty present at all sessions. These discussions are often student-led and prepared using the three questions that each student generated for discussion. Having students facilitate discussions tends to relax the learning climate and encourages authentic conversations; students are more willing to exchange ideas, raise questions, and listen to different perspectives when it’s peer-to-peer. And, they always have a way of getting a good laugh out of us.

- Student engagement in peer-group work: After students finish reading the book, they, along with members of their book group, put together an activity to teach the class something about the topic or issue of their book. Last semester, some book groups posed a problem for the class to solve, created a Kahoot, showcased an exhibit, and designed a jeopardy game. These activities were fun, creative, and learning-driven.

- Practicing what writers do: To conclude this project, students work through the writing process of generating ideas, drafting, giving/receiving feedback, and revising to compose a book review, which then gets published in their ePortfolio.

As we settle in for another semester of remote instruction, having conversations in the classroom is more important than ever to tackle pandemic isolation and learning, and using book groups is one way to do that. When students engage with each other in weekly discussions and peer-work, they share not only new ideas but also a friendship that seems unlikely in the middle of a pandemic.

Crystal O. Wong, EdD, began her teaching career in the San Francisco Unified School District as a K-5 music, literacy, and classroom teacher before starting a second career at San Francisco State University, where she teaches in the Writing Program. Dr. Wong has won several awards, including the university-wide First-Year Teaching Award (2019) and the Liberal & Creative Arts Excellence in Teaching Award (2020). She has a passion for learning and effective teaching.

References

Garrison, D. Randy, Terry Anderson, and Walter Archer. “Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education.” The internet and higher education 2, no. 2-3 (1999): 87-105.

Orlov, George, Douglas McKee, James Berry, Austin Boyle, Thomas DiCiccio, Tyler Ransom, Alex Rees-Jones, and Jörg Stoye. “Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic: It Is Not Who You Teach, but How You Teach.” NBER Working Paper 28022 (2020).

Rienties, Bart, and Bethany Alden Rivers. “Measuring and understanding learner emotions: Evidence and prospects.” Learning Analytics Review 1, no. 1 (2014): 1-27.