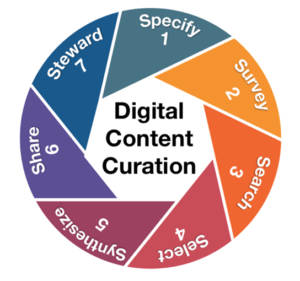

In our 24/7, always-connected world where we are inundated with information from all sides, the ability to identify quality resources to inform our research and actions has become a major focus in higher education. Digital Content Curation, as it is called, is something that many faculty believe they should be teaching their students, but they are not sure where to start. I have created a model of Digital Content Curation that faculty can use to help students sharpen their digital literacy and research skills (Garner, in press).

Specify

At the beginning of any journey, it is important to specify the desired destination. This is also true when looking for information. Students should start by stating what they want. The key questions for them to answer are:

- What types of questions am I trying to answer as a result of my search?

- What are the criteria that define a successful search?

To answer these, students should: (a) Draft specific research questions, related to their topics of investigation, or (b) Generate hypotheses related to their area of investigation. These questions will guide their further research.

Survey

The survey phase is focused on choosing the tools that will be used to explore the Internet.

There are a variety of tools that can be used to seek the information and answers needed at any given moment. If searches are related to common, everyday topics, then “Googling it” would suffice. At the same time, however, if searches are related to disciplinary or research topics, those with greater levels of nuance and sophistication, then students should be equipped to take advantage of varied and specialized search tools (e.g., EBSCOhost, PsycINFO, PubMed/Medicine). The key questions that the student should answer at the survey level are:

- What type of information is being sought (e.g., general information queries, academic journals, books, conference presentations, video/audio)?

- What subscriptions to academic databases are available?

It is important for student-scholars to be fully aware of the search tools available in their academic disciplines. To facilitate this, faculty could, for example, require students to submit initial listings of those resources gleaned from a variety of search databases (e.g., Google Scholar, WorldWideScience, ResearchGate). This beginning step would serve to illustrate similarities and inconsistencies between the selection and rankings represented by search tools in response to common query terms.

Search

The next step is to search for sources. While everyone knows how to Google for information, many do not consider how they are crafting their search terms and queries. When Internet information was limited, it was often better to use very general terms to capture all possible sources, but now it is better to start with very specific terms to eliminate poor sources. The key questions that guide students at the search phase are:

- What types of search terms and queries will yield the best results?

- What are the expectations for this search process (e.g., number of potential resources, variety of sources?)

Faculty can help students become better, more efficient searchers by providing demonstrations of how different search terms yield different resources, from poor to good. Faculty should include terms that give results for websites that feature erroneous content to demonstrate the need to be mindful of how one is searching for information. Faculty in online classes can shoot a narrated screencast video of different searches to teach students how to craft searches in their field.

Select

After gathering a collection of information gleaned from digital resources, the challenge becomes one of selecting the most relevant and accurate content. Engagement in this process requires a thoughtful and systematic examination of the available information with an eye toward finding themes, inconsistencies, and newly identified pathways for further searching as a way of strengthening the final product. The key questions that guide activity at the select level are as follows:

- What types of strategies could be used to assess and verify the quality of collected information?

- Is there an openness to the possibility that final conclusions might be contrary to or change initial hypotheses?

A viable search process should result in a listing of resources worthy of further examination and possible inclusion in the developing final product. Now as we move into the select phase it may be advantageous to require a writing plan that includes topics to be discussed and the relevant resources. This could take the form of a word document or a graphically-oriented “Mind Map” (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mind_map for more information). In this way, students are encouraged to create a plan of attack and identify their chosen resources. There are variety of online tools to assist students in creating these graphic representations of their planned project, with Coggle being one of the best.

Here is where you want to help students select content wisely. There are a number of good websites that can help faculty teach students about poor reasoning. One is a good blog by Gary N. Curtis called Fallacy Files that uses modern headlines as examples. Another is an explanation of how science critiques claims based on work by Carl Sagan.

Synthesize

Systematic research procedures should culminate in a process of summarizing and synthesizing the works found. Faculty often require students to draw the results of their research into a report, but do not require students to summarize individual works. But the ability to summarize an author’s position is critical to validating its veracity, as it often alerts students to gaps in the author’s reasoning. When a student cannot piece together an author’s argument, it might be that the author’s work does not have a coherent argument. Thus, resource assignments should include a requirement to summarize the arguments of the works used.

Share

After synthesizing results of the process thus far, the major task then becomes one of determining the most effective and appropriate format for distribution to external audiences. Historically, in higher education, the gold standard for sharing has long been the research paper (with subsequent conversion to a journal article, book chapter, or presentation). Although this pattern is likely to continue, researchers can now consider alternate ways to share their work in digital contexts (e.g., website, blog, wiki, podcast, video, audio, social media, electronic journals, academic social networking sites). The key questions that guide activity at the share phase are:

- What are the primary and secondary locations that are intended destinations for this content?

- Are additional skills or resources necessary to take full advantage of the exposure and dissemination possibilities of the chosen venues?

As educators, we are all vitally interested in having our students master the content in our academic disciplines and achieve the identified learning outcomes. Now consider the possibility of a value-add: Students demonstrate what they have learned through the creation of an authentic digital product (e.g., website, video, blog, infographic). The Internet offers a vast collection of resources and tools in each of these areas, along with tutorials and step-by-step directions.

Steward

Students normally forget about the research sources they used once the class is done. But students should be encouraged to become “intellectual hoarders” by preserving their sources in a format that can be used in later classes and even after college. As digital creators, curators, and consumers, there will be an ongoing struggle to determine which content should be saved (i.e., short-term and long-term) or discarded immediately after use. These decisions are subject to considerations about access (i.e., getting back to saved content on an as-needed basis), capacity of storage options, cost of storage, and the level at which saved content is secure from outside sources.

Stewarding information is more than just saving it as files on computers, CDs, or the cloud. It also means developing an organizational system that allows the information to be found quickly. It could be as simple as a Word document set up as an annotated bibliography of sources the student has used. This allows the student to later survey those sources to see what can be of benefit in research. A more sophisticated approach would be notetaking software such as Evernote, which allows students to post a summary of each resource, or even the resource itself attached as a PDF, along with tags that allow the student to query their resources with search terms. Take a look at this tutorial from Kris O’Brien on how to use Evernote to organize research and consider sharing it with your students.

Consider the possibility of guiding your students through the process of digital content curation as a way of helping them learn and practice these disciplines. Knowing how to accomplish that task is one that will serve them well throughout their personal and professional lives.

This article first appeared in The Teaching Professor on September 9, 2018. © Magna Publications. All rights reserved.

Brad Garner is the director of faculty enrichment at the Center for Learning and Innovation at Indiana Wesleyan University.

Reference

Garner, B. (in press). Digital content curation: A 21st century life skill. Newcastle Upon Tyne, UnitedKingdom: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.