A college student opens the double doors and walks into a large conference room full of 65 long tables, set end-to-end and stacked six rows deep. Taking it all in, he asks his classmate, “How do we know where to put our projects?” before realizing large instructions with randomly assigned locations are projected up on the screen for all to see. He carefully places his project down onto spot #45, along with his required “Executive Summary,” a two-page document that provides his self-assessment and rationale about why he chose his project, what class content it caused him to research and learn more deeply, and how his project directly helped fulfill the four overall stated course outcomes.

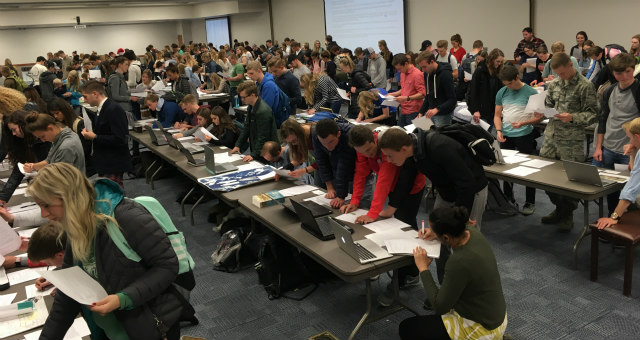

After giving students a few minutes to get situated, the professor stands at a podium, “Welcome to our project fair! You all should have placed your project and executive summary on your assigned number. Now, it’s time to evaluate your peers. You each have been assigned four random numbers that represent the projects you should peer evaluate. Pick up the peer evaluation sheet at the front of the room, and spend 15 minutes with each project, following the rubric and providing your feedback and scoring for each section of the project requirements.” For the next 45 minutes, a few hundred students shuffle from project to project, using a Likert-scale scoring assess how well a project met the rubric criteria. It’s an exciting, educational, and informative hour.

Afterward, the professor and his teaching assistants enter the peer scores into a spreadsheet, dropping the lowest score and averaging the other three, calculating each student a combined overall peer score. Then, the professor and his TAs follow the same pattern and rubric and give a teacher rating of the project, providing combined feedback to the student. Thus, when the project is finished, the final score is a composite: the first part is based on the student’s own self-assessment of the project, the second part based on a peer assessment of the project, and the last part from a teacher assessment of the project.

The project fair, described above, is an example of what’s known as multiple perspective assessment. In the past few decades, higher education has sought to implement more outcomes-based, self-regulated, and community-based learning. Multiple perspective assessment incorporates many of these elements, and others, into a more holistic evaluative process. Fundamentally, multiple perspective assessment includes three perspectives:

- The student’s own (self-assessed)

- The student’s peers (peer-assessed)

- The student’s professor (teacher-assessed)

The weight each category carries can and should vary, depending on the assignment and its purpose. Some may weigh the teacher portion more heavily, others the peer, while others make the self-assessment weighted the most. The important thing is for the assessment to include all three in some degree.

Although teacher assessment is standard educational practice, the crux of multiple perspective assessment involves students in both peer assessment and self-assessment. These two areas are often unexplored or underutilized by many university teachers. There are pros and cons to each, to be sure (as is true with teacher-based assessments), but many of the positives outweigh the negatives.

Other than providing a more holistic view, why should professors consider ways to include self-assessment or peer assessment? Self and peer assessment procedures help students to reflect on their own work or that of others, evaluate it against set criteria, and provide feedback (both consciously and subconsciously) for themselves as they participate in the process. All of this helps them to learn and improve their own work. As Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick (2006) summarized: “A key argument is that students are already assessing their own work and generating their own feedback, and that higher education should build on this ability….students are seen as having a proactive rather than a reactive role in generating and using feedback, has profound implications for the way in which teachers organize assessments and support learning.”

If the idea of multiple perspective assessment makes you think, “NO WAY would I let students provide a grade for themselves or each other, even based on a well-defined rubric,” that’s understandable. I would encourage, however, to yet consider using self-assessment or peer-assessment in a formative fashion rather than a summative one. Commenting on some of the research in this field, Maryellen Weimer noted that “self-assessment is not the same as self-grading. Rather, students are looking at their work and judging the degree to which it reflects the goals of the assignment and the assessment criteria the teacher will be using to evaluate the work.”

Self-reflection, self-regulation, peer-to-peer feedback, and hearing/learning from multiple perspectives are essential skills that reflect higher education values. However, these skills are often not explicitly taught or proactively implemented in some university courses. Multiple perspective assessment helps foster these essential skills, and many others, while providing a more holistic view, whether as formative or summative assessment. This approach is especially useful in project-based learning, term research papers, or in large-enrollment classes where many students can anonymously assess others work and share it with a large group. As one student said of the project fair, “This is my favorite day of the semester. Being able to see and evaluate so many others’ projects is super cool. I am really glad we do this.” It is my hope you may think of ways to incorporate multiple perspective assessment into your courses and be glad you did it, too.

References:

Nicol, David J. & Macfarlane‐Dick, Debra (2006) Formative assessment and self‐regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice, Studies in Higher Education, 31:2, 199-218

Weimer, Maryellen. “Self-Assessment Does Not Necessarily Mean Self-Grading.” Faculty Focus. Retrieved from https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/educational-assessment/self-assessment-does-not-necessarily-mean-self-grading/

Photo courtesy of author.