Can we teach entrepreneurship? This is a question that has vexed entrepreneurship scholars for generations, and it still is a question that is relevant today (Klein & Bullock, 2006). The Austrian economist Ludwig Von Mises (1949) who is one of the main precursors of the field, argued that entrepreneurship is neither taught nor learned, for entrepreneurs see the world differently than others, perceiving what others don’t, breaking new ground where others are just “doing” what has been done before. As such, entrepreneurs come to be depicted as those who are dealing with novelty and complex scenarios, and they make decisions in ways that go beyond the “rational” models of normal social science. In many ways, entrepreneurship is treated as an inherent trait or skill that is not formalizable, and thus it is a behavioral trait, not an acquired skill.

This would fly in the face of the modern institutional environment of entrepreneurship research and education. For example, entrepreneurship is a field of study that is growing in business schools. Many currently offer minors in entrepreneurship or even majors, and some are offering PhD courses in Entrepreneurship to train the next generation of scholars and teachers in the field. Still, if Entrepreneurship is an inherent trait or talent, are we wasting resources and time, both of our students and ours, by attempting to teach what cannot be taught?

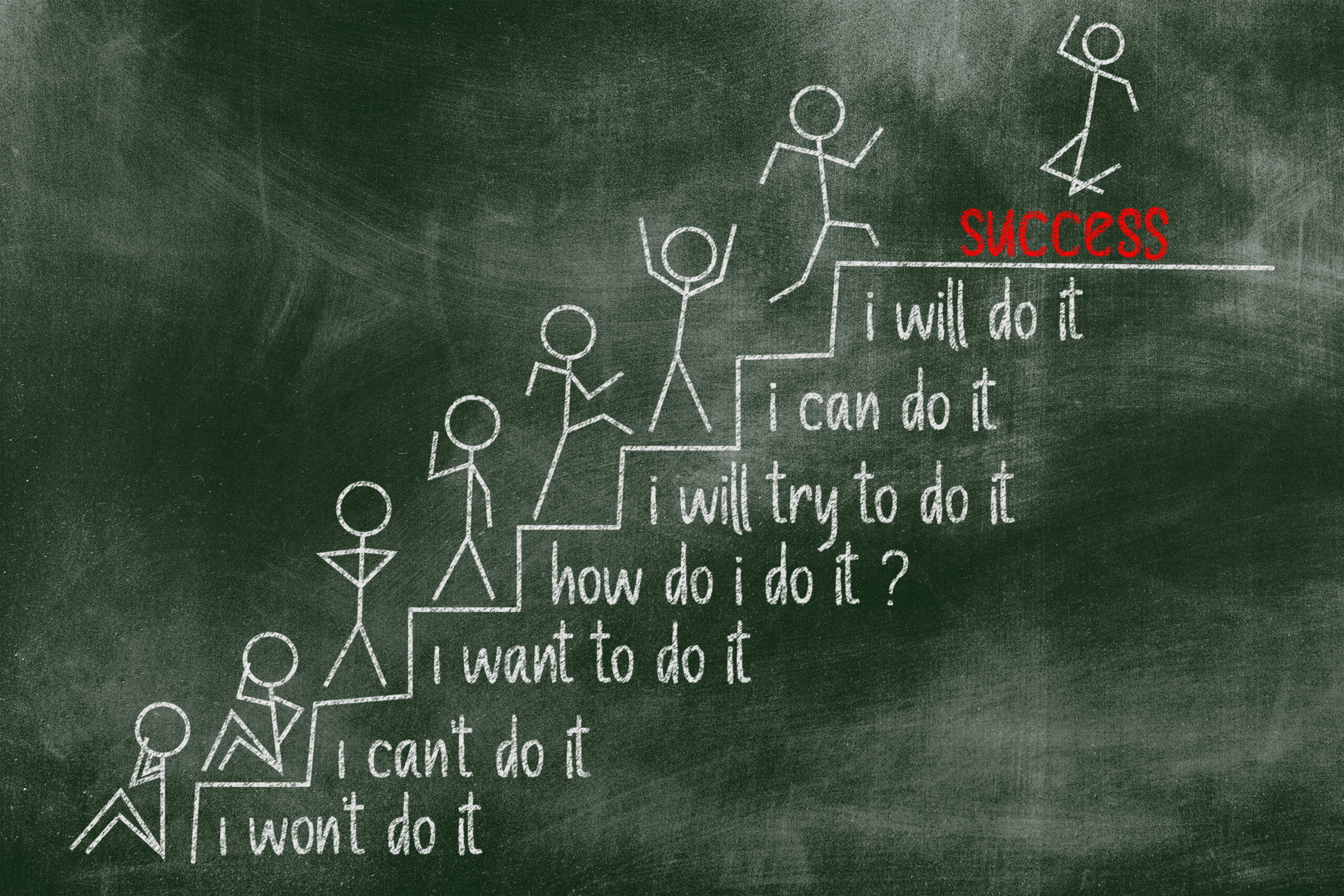

Such a question is not limited to the field of entrepreneurship itself. Entrepreneurship can be seen as a special case of the more general debate of “nurture” vs “nature” in teaching and learning. If intelligence and abilities are fixed from the outset, the teacher’s job becomes one of weeding out those who don’t have the innate potential and providing those with innate potential the information and tools to develop and refine what they already have. Your students will either be good Mathematicians, or they won’t. Actors will be good at playing a role, or they won’t. Singers will sing, or they will bother us making sounds we do not want to hear, etc, you can see the point. For both instructors and their students, that means adopting a mindset that avoids persistence in favor of pivoting and changing course. Early failures and failed first trials are not interpreted as a diagnosis of what could be done, and are instead seen as proof of what can’t (Yeager & Dweck, 2020).

This is where a growth mindset intervention has its place. Growth mindset theories question the claim that intelligence, talent, and skills are simply inherent traits of individuals, and see instead that education, training, and learning are not only tools to explore the potential that already exists, or even develop untapped potential, but they also may be the source of supposed “talent” (Yeager et al., 2020). With a growth mindset even talented individuals benefit and can advance their field, skills or capabilities. As Dweck (2018) showcased, even Olympic athletes benefit from a growth mindset. Athletes such as Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods pushed themselves, analyzed their performance, and addressed their weaknesses, achieving greater performance through persistent effort.

This example can be extended to different scenarios, such as music. A case of note is Avenged Sevenfold’s singer Matt Shadows. After a quick headstart into fame pioneering the Metalcore genre, Shadows quickly learned that technique and discipline are the crucial bedrock for his (in the author’s opinion) amazing singing abilities. In a recent interview for the Finnish magazine Chaoszine (2024), he mentioned how he developed a set of routines to better his singing that range from a well-planned diet to the way he sleeps. If talent was all he had, he would simply get on stage and sing. Instead, he developed what can be seen as a growth mindset where consistent training, practice, and care were the bedrock for what he did.

Where does entrepreneurship come into play in all of this? As my argument goes, for starters even if talent is somewhat inherent, it will not turn into successful outcomes if not for the possession of a growth mindset. Beyond that, even if not first showcased as talent, skills do emerge if effort, motivated by a growth mindset, is present. Research has showcased how a growth mindset improves entrepreneurial self-efficacy (defined as the beliefs one has about his ability to bring about a desired outcome) in higher education students, increasing their task persistence and career interest (Burnette et al, 2020). In other settings similar results were reported, where growth mindset interventions created positive feedback loops in academic performance (Limeri et al., 2020). Both cases reinforce the argument that for entrepreneurs or students reducing how much failure impacts decisions to persist is crucial if capabilities to succeed are to be achieved, and entrepreneurship education would benefit from taking a more experimental, trial-based approach strengthened by a growth mindset.

For us teachers, that implies that our role is greater than what a “nature” based perspective on education would allow. Teaching and learning now have more than a dimension of giving students knowledge that they’ll turn into what they are already capable of turning it into (basically showing a student who already has a propensity to be good in Mathematics what calculus is). Education now becomes a quest for developing in students the skills, discipline and mindset needed for their successful learning paths. In less abstract terms, teaching is not reproducing knowledge, but also teaching how to acquire knowledge or how to start a practice (Seaton, 2017).

For entrepreneurship educators, that is translated into a competence development approach for how they educate their students. The intended outcome (entrepreneurial value-creating activity) has as its input the myriad of competencies developed in training for taking up the tasks and challenges associated with the entrepreneurial journey (Mawson & Simmons, 2023). As previous research showcases (Camuffo et al., 2020), entrepreneurs become comparatively more successful when failures are absorbed and used as a means for diagnosing what needs to be changed. Entrepreneurs, much like academics and students, are working in a trial-and-error environment where what is important is not to immediately succeed. Immediate success, although desirable, does not let the entrepreneur (or student) learn how to adapt to unforeseen changes and failures.

For educators in general, the situation is not that much different. We need to show our students that they can be more than what their current limits impose on them, and that is where a growth mindset intervention comes into play. Mathematics, entrepreneurship, and acting, should not be inherently reserved for those who showcased these skills from the outset. Students can grow into those roles by using failure as a form of diagnosis for future learning. One of the ways to do such is to realize such interventions in the classroom entails using coursework as a way of showcasing how students may change their own self-efficacy (as their self-perceived ability to achieve a goal or complete a task). Here are general principles for growth-mindset interventions:

- Use assignments at a greater frequency to assess progress and give early feedback (Ex: Weekly mini-tests come into play here).

- When providing feedback, not only say what was wrong but provide a clear blueprint of what the student can do to correct previous mistakes (Ex: When delivering a corrected test to the student, consider handling it with a note on his strengths and weaknesses, and what you would like him to study to avoid the same mistakes on the next test).

- Emphasize how past failure can be traded for future success through persistent trials. (Ex: Cumulative tests can be useful here, where knowledge from one assignment builds into the next one).

They can be seen as practical cues for teaching students, likely entrepreneurs or not. In education, science or business, failures may be seen as negative feedback in the short-run, but can be used as a tool for positive improvement in the long-run. Students and entrepreneurs with a growth mindset do not see failure as a simple one-time event that signals the need to pivot away from the subject, topic or field. Instead, a growth mindset enables them to interpret failure as a learning cue that showcases the need to change their strategies, reassess their assumptions and reallocate their efforts to try again. Mathematics, entrepreneurship, and acting, should not be inherently reserved for those who showcased these skills from the outset, and fear from failure should not stop someone from trying. Once again, it is to be emphasized that students can grow into those roles through persistent (but directed) effort, and we better help them try, for how many might-have-beens could have been realized, if not for a lack of a growth mindset?

Luan Valério is a PhD Student in Entrepreneurship at Baylor University’s Hankamer School of Business in Texas, having previously obtained a BA in Economics back in his home country, Brazil. His research interests encompass strategic entrepreneurship, decision-making under uncertainty and entrepreneurial education.

References

Camuffo, A., Cordova, A., Gambardella, A., Spina, C. (2020). A Scientific Approach to Entrepreneurial Decision Making: Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial. Management Science, 66(2), 564-586.

Chaoszine Magazine. (2024). My Story As Metal Frontman #87: M.Shadows (Avenged Sevenfold). In: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tpYgwdE82jo

Dweck, Carol. (2018) Mindsets: Developing Talent Through a Growth Mindset. Olympic Coach, 7, n.21.

Limeri, L.B., Carter, N.T., Choe, J. et al. (2020). Growing a growth mindset: characterizing how and why undergraduate students’ mindsets change. IJ STEM Ed 7, 35.

Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2020). What can be learned from growth mindset controversies? American Psychologist, 75(9), 1269–1284.

Burnette, J. L., Pollack, J. M., Forsyth, R. B., Hoyt, C. L., Babij, A. D., Thomas, F. N., & Coy, A. E. (2020). A Growth Mindset Intervention: Enhancing Students’ Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Career Development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 44(5), 878- 908.

Klein, Peter G. & Bullock, J. Bruce, (2006). “Can Entrepreneurship Be Taught?,” Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, Southern Agricultural Economics Association, vol. 38(2), pages 1-11.

Klein, Peter G. & Bylund, Per. (2014). The Place of Austrian Economics in Contemporary Entrepreneurship Research. Review of Austrian Economics, 27, 259-279.

Mises, Ludwig Von. (1949). Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. The Ludwig Von Mises Institute.

Mawson, S., Casulli, L., & Simmons, E. L. (2023). A Competence Development Approach for Entrepreneurial Mindset in Entrepreneurship Education. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 6(3), 481-501.

Seaton, F. S. (2017). Empowering teachers to implement a growth mindset. Educational Psychology in Practice, 34(1), 41–57.