Have you been thinking about purchasing a subscription for The Teaching Professor? Today is your lucky day! Here’s a recent, free article directly from The Teaching Professor. Check out a monthly, one-year, two-year, or a three-year subscription!

This article first appeared in The Teaching Professor on January 22, 2024 © Magna Publications. All rights reserved.

Mental health concerns have emerged as a heightened concern, gaining recognition among faculty members and becoming an integral aspect of academic discussions. This shift in focus has been particularly notable in the wake of the ongoing pandemic, prompting educators to find ways to support student well-being.

In higher education, where intellectual growth and academic achievement often take center stage, the mental well-being of students is a subject too frequently relegated to the periphery. Yet, as students navigate the landscape of university life, it becomes increasingly evident that the mental health of our students is not a sidenote but a fundamental chapter in their journey. The transition from high school to university represents a period of change, often marked by newfound freedoms and responsibilities. But it also brings with it an array of challenges, particularly in the realm of mental health. The stigma surrounding mental health issues and the reluctance to openly discuss them openly exacerbate the situation, leaving many students to silently grapple with their emotional well-being. As educators, we hold a unique position of influence in our students’ lives, one that extends beyond the classroom (Trolian et al., 2022). Thoughtfully harnessed, this influence can become a powerful tool in breaking down the stigma and showing students that their mental health matters.

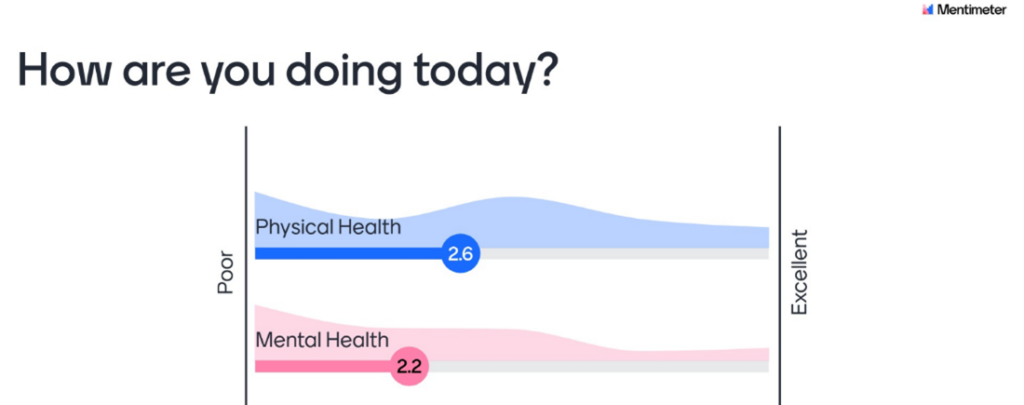

To this end, I recently decided to start each class period with an anonymous, real-time Mentimeter survey asking, “How are you doing today?” There are two response areas—physical health and mental health—and students respond on a five-point scale with “poor” and “excellent” as the anchors (Figure 1).

Over time, the survey became a normal part of the routine. The survey would be on the screen while students settled into their seats. I recorded the scores each week and would discuss how the current class compared with the previous class. I would ask students why they thought the scores were lower or higher. On one occasion, the mental health scores were almost a whole point lower than in the previous week. The students shared that there were several evaluations in other courses that were taking a toll on them. That prompted me to modify the plan I had for the class and give students some time to attend to other coursework.

At the halfway point of the term, I shared the results of the survey for the first six weeks in a line graph. I asked the students what they thought about the scores and whether they noticed any patterns or trends. They noted that both physical and mental health scores were lower around midterms. We had a brief chat about strategies they could use in anticipation of or during high-stress moments. Students shared that going for a walk, taking a break, seeing friends, and getting a good night’s sleep might be helpful.

As I continue to use this practice in my classroom, the next phase will be to gather information about the students’ experience. What’s it like for them to pause and reflect on their physical and mental health before class? If the scores are low does that make the class more difficult? While I hope the anonymity of the survey helps students to be truthful with their responses, it’s difficult to assess whether students feel comfortable enough to be vulnerable and rate their physical or mental health as “poor.” Gaining a sense of their experience will likely influence how I move forward with the surveys. One student shared that they were “surprised to see the survey after the first class, I thought it was just some kind of icebreaker, I was like, oh, she actually cares.”

While the administration and logistics of a survey like this are simple, it sends students a profound message: that you genuinely care about their well-being. As educators, we understand that the academic journey can sometimes be isolating, but when students see that their peers share similar struggles, it encourages empathy and mutual support (Park et al., 2020). Moreover, discussing this shared data in class validates their experiences, reinforcing the idea that your classroom is not just a space for academic growth but a community where each student’s well-being is valued.

By integrating questions about both physical and mental health into pre-class surveys, we normalize the conversation around mental well-being—a critical step in reducing the stigma around mental health. In many instances, conversations about physical health are commonplace, while mental health discussions remain unspoken. But posing questions about both stresses an important truth: mental health is an integral part of our overall well-being. It underscores that addressing mental health is not taboo but a legitimate concern. This shift in perspective encourages students to acknowledge and possibly seek help for their mental health, fostering a more compassionate academic environment.

Our role as educators extends beyond the dissemination of knowledge. Students’ satisfaction hinges on more than just our expertise; it’s equally influenced by our ability to create a supportive learning environment (Geier, 2021). This means that every one of us has the power to positively influence academic culture. Implementing strategies like well-being surveys signifies our commitment to holistic student development. It tells students that we are invested in their welfare—personally as well as academically. Together, we can shape an academic landscape where the pursuit of knowledge coexists with the pursuit of well-being, fostering resilient and empowered learners who are prepared to thrive in both their academic pursuits and life beyond the classroom. So, if you’re wondering how you’ll start your next class, consider asking your students, “How are you doing today?”

References

Geier, M. T. (2021). Students’ expectations and students’ satisfaction: The mediating role of excellent teacher behaviors. Teaching of Psychology, 48(1), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628320959923

Park, S. Y., Andalibi, N., Zou, Y., Ambulkar, S., & Huh-Yoo, J. (2020). Understanding students’ mental well-being challenges on a university campus: Interview study. JMIR Formative Research, 4(3), e15962. https://doi.org/10.2196/15962

Trolian, T. L., Archibald, G. C., & Jach, E. A. (2022). Well-being and student–faculty interactions in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(2), 562–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1839023

Danielle Dobney, PhD, is an assistant professor in kinesiology and physical education at the University of Toronto. A certified athletic therapist and registered kinesiologist, she holds graduate degrees in rehabilitation sciences from the University of Toronto and McGill University. Since 2014 she has been an athletic therapist for Canada Basketball and currently works with the senior women’s basketball team.