Reflecting on our approach to course design—particularly with attention to how we build community and cultivate belonging—couldn’t come at a more crucial time. Since the turn of the millennium, with the publication of How People Learn (Bransford et al.,1999), the importance of these dimensions in creating an effective learning environment has been well-documented. And, as headlines since the pandemic continue to remind us, our students have never felt more isolated and alone.

Loneliness has been linked to several serious health issues—from anxiety and depression, to increased stroke risk, suicide and, yes, shorter lifespans. The issue is especially acute for young people who are almost twice as likely to say they feel lonely compared to people over 65. In May 2023, U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Vivek Murthy, sounded the alarm when he declared loneliness a national “epidemic.”

Supporting student well-being is not about going through the motions of an icebreaker or a “get to know you” exercise. What’s striking is that when grounded in evidence-based teaching practices, effective courses foster a greater sense of belonging, increase student confidence in their ability to graduate, and create more opportunities for feedback and encouragement (Tyton Partners, 2023). Intentional course design, it turns out, emphasizes many of the very same things that support student well-being (Slavin, Schindler, & Chibnall, 2014).

The good news is educational technology is making it far easier to not just improve academic outcomes, but to help students thrive through what should be one of the most formative experiences many of us will have in our lifetimes.

Taking the temperature

Evidence suggests that checking in with students on how they’re feeling, even for a moment, has significant benefits (Klem & Connell, 2004; Zengaro & Zengaro, 2022; Burke et. al., 2022). Classroom response systems make the practice of regular “temperature checks” an impactful and efficient activity in even the largest classrooms.

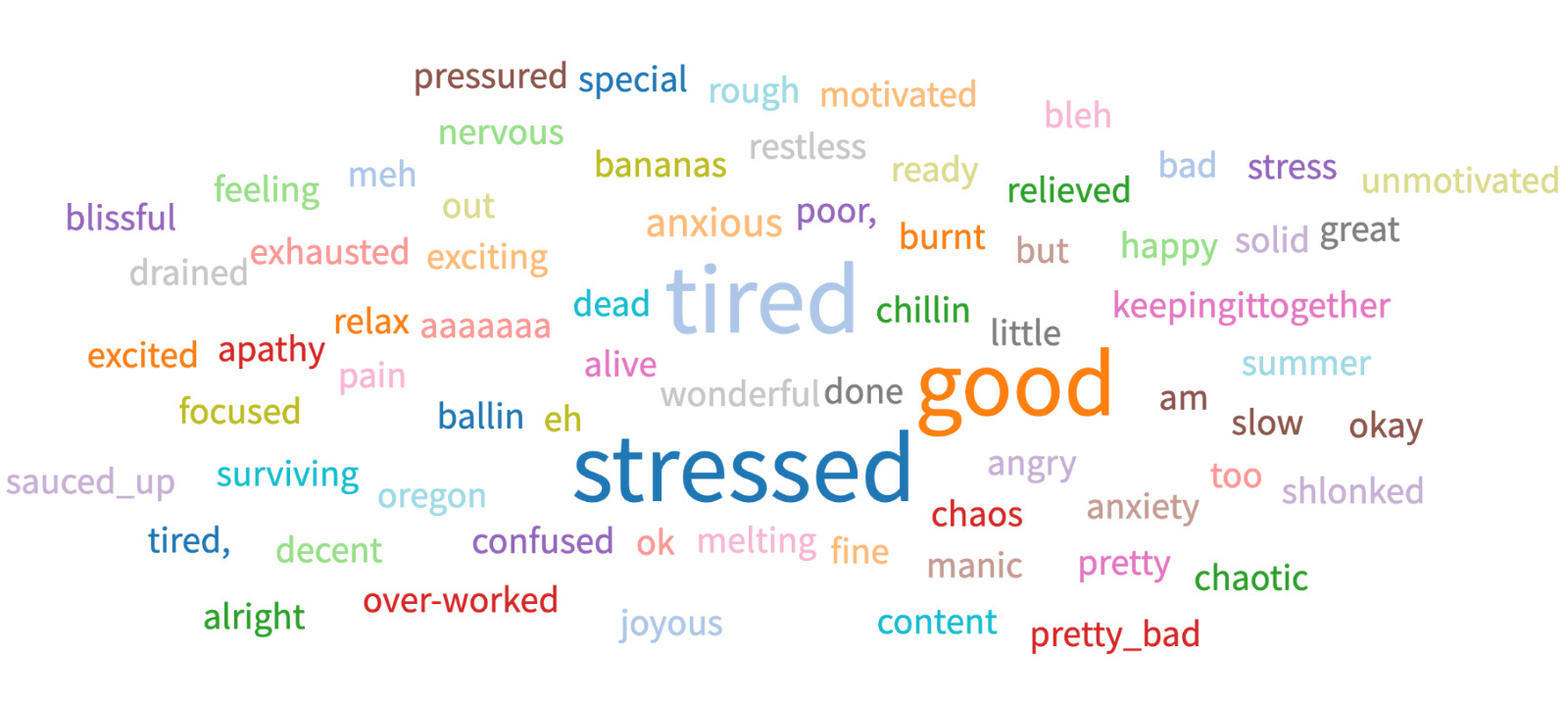

At the start of a class you might ask: How are you doing? Academically? Socially? Emotionally? Single-word responses can be turned into a word cloud, giving students a quick visual summary of how they are feeling relative to their peers, reinforcing that even on our bad days we are usually not alone.

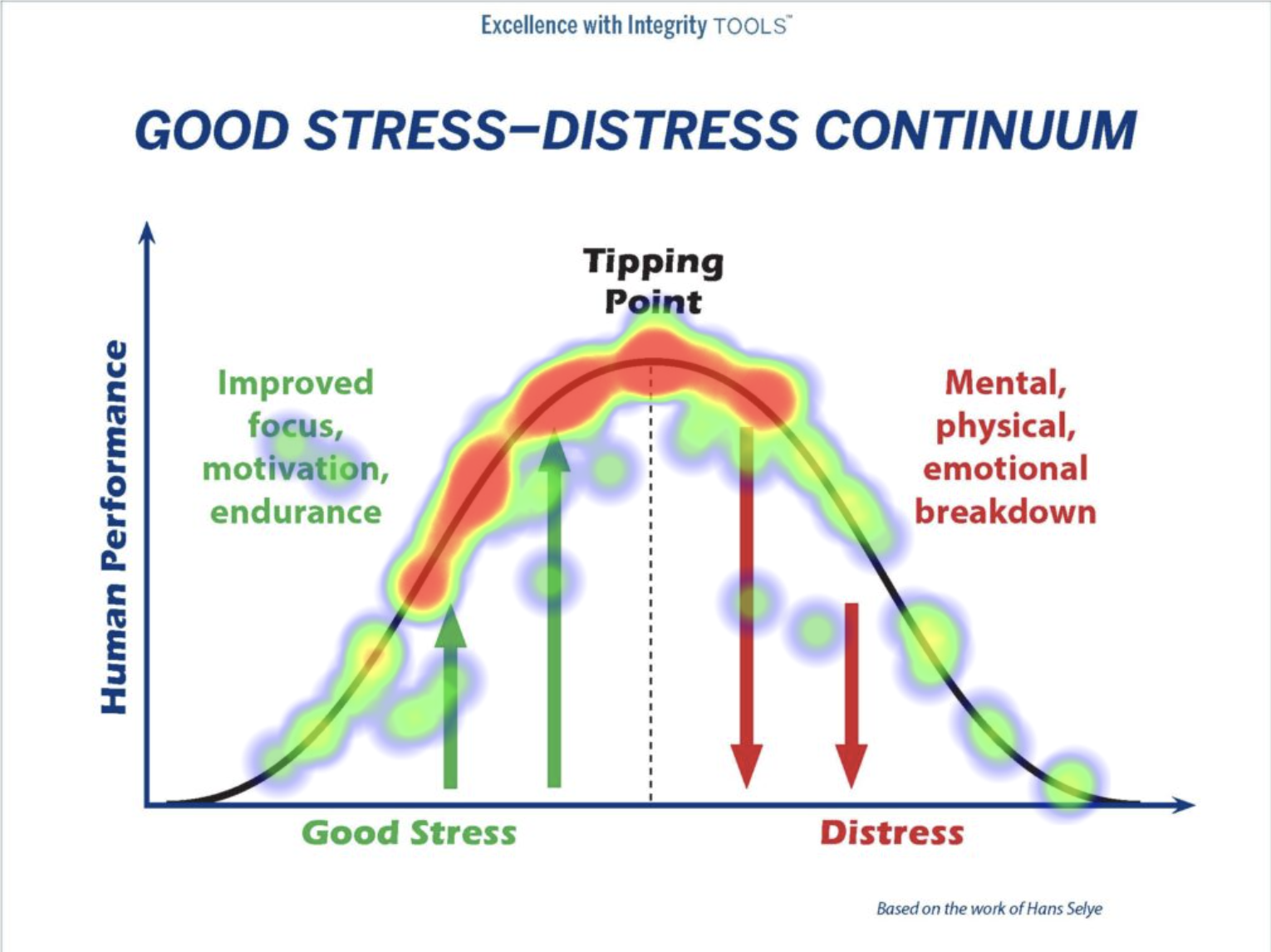

The use of click-on-target questions, where individuals click on an image (think emoticons or weather symbols) and capture a heatmap is an effective way to show patterns and identify trends, providing opportunities to comment and discuss outliers with the class. These questions can also be used as moments for teaching. For example, to make the point that stress can sometimes be useful, you might ask students to click on the “Good Stress-Distress Continuum.” Based on the work of Hans Selye, a pioneering stress researcher, this gets students to identify and place their stress on a continuum from “good stress” to “distress.” In many cases, what they’re feeling may not be necessarily bad, and providing this resource helps to improve their focus and motivation. After all, succeeding academically in college should take effort!

Even so, stress will often get the best of us. Since mental well-being is foundational for effective learning (Seligman, 2012), it’s important to acknowledge when students aren’t doing well. You might ask your class to take a few deep breaths before moving ahead or challenge them to think about one thing they’re grateful for to gain perspective. It’s also the perfect opportunity to reinforce that admitting we’re struggling is a sign of strength, not weakness, and to highlight the resources available to support student mental health.

Create a back channel

An open, anonymous discussion that runs continuously throughout the class is one of the most effective ways to create a sense of community among students. Back channels give students the opportunity to have their own conversations, to share questions and comments, and, yes, memes and jokes that, in our experience, are a strategy that allow students to shape the culture of the classroom. Far from being a distraction, effective backchanneling empowers students to take control of their own learning (Peters & Toledo, 2010).

It might seem counterintuitive, but a rich backchannel can make individuals more inclined to speak up. The trick is to give students license to interrupt when an important question or comment arises or assign specific individuals to monitor the discussion and check-in periodically.

Beyond creating a more informal learning environment, back channels serve another important function: They shine a light on our assumptions and misconceptions. Are students struggling in areas we didn’t anticipate? Are there memes or analogies students are using that are more effective in getting across the things we think are important? In this way, backchannels serve as a formative assessment for instructors to identify ways to improve the delivery and impact of our teaching.

Making learning visible

We are likely familiar with how regular, low-stakes assessments correlate with improved academic outcomes (Crede & Sotola, 2021). Student response systems take these benefits a step further by helping students visualize their learning within the context of the larger community.

In bigger classes, it’s all too easy for students to feel anonymous or left out. Conducting regular assessments using real-time polls and quizzes allow students to understand how well they’re doing and where they may need to place additional effort. Making the results visible offers another important yet subtle cue: it reminds students that even when they are struggling, chances are they aren’t the only ones.

Formative assessment is an equally valuable if not underused tool in the educator’s toolbox. If we use the analogy of a garden, formative assessment provides the nourishment and support a plant needs to grow, whereas summative assessment merely measures how much growth has taken place. Formative assessment is about getting students to reflect on their learning, to identify their strengths and weaknesses, and consider new approaches they might use to improve in the future. Incorporating reflection exercises or exit tickets also provides moments for students to take stock of how far they’ve come, helping them cultivate a growth mindset while increasing the likelihood of retaining what they’ve learned.

Feedback and early intervention

It’s important to consider whether our current approaches to assessment support or detract from student well-being. There is plenty of evidence to suggest that infrequent, high-stakes assessments place many students in a threat scenario, increasing cortisol levels in the bloodstream, a stress hormone closely associated with underperformance (Heissel et. al., 2021). High-stakes exams may in fact do a better job of measuring how well students cope with test taking, rather than assessing actual learning.

Frequent assessment, on the other hand, offers students the opportunity to practice applying knowledge regularly, knowing that a poor grade on a quiz won’t jeopardize their ability to pass a course. They also allow instructors to generate a steady stream of signals we can use to support our students. Researchers at Charles Sturt University in Australia used a failing grade or those who were on track to receive a “near miss” in the first few weeks of the semester to target at-risk students with extra support. As the team found, small but critically timed interventions like this can make the difference between success and failure.

The added benefit of frequent assessment is the chance to provide regular feedback and encouragement. But not just any feedback. Great instructors go a step further by asking more of their students. In a field study involving schools across the United States, teachers gave students the opportunity to revise an essay they’d written. One group received general comments while the second was told, “I’m giving you this feedback because I have very high expectations and I know you can reach them.” Forty percent of those who’d received the generic feedback chose to revise their papers, while almost 80 percent of students in the ”wise feedback” group did the same and made more than twice as many corrections. How we deliver feedback makes an enormous difference to student motivation and how supported they feel by their instructors.

Summing up

Creating connection, belonging, and demonstrating care is arguably more easily accomplished when these activities are organized around the work of the course itself, rather than something separate. And that’s a good thing. After all, supporting student well-being deserves more than just a cursory nod. By embracing evidence-based teaching practices, and emphasizing social connection and shared experience, we can become architects of courses that nurture more than just academic success.

Dr. Demian Hommel, PhD, teaches introductory and upper-division human geography courses in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences at Oregon State University. He is also a fellow for the institution’s Center for Teaching and Learning, working to push the mission of excellence in teaching and learning across his campus and beyond.

Dr. Bradley Cohen, PhD, is the chief academic officer at Top Hat where he provides leadership and advocacy for personalized, inclusive and equitable teaching practices within the higher education community. Prior to joining Top Hat, Cohen served as the Chief Strategy and Innovation Officer at Ohio University and as the head of the Center for Educational Innovation and Associate CIO for Academic Technology at the University of Minnesota.

References

Burke, K., Fanshawe, M., & Tualaulelei, E. (2022). We Can’t Always Measure What Matters: Revealing Opportunities to Enhance Online Student Engagement Through Pedagogical Care. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 46:3, 287 – 300.

Cohen et. al (2014). Breaking the Cycle of Mistrust: Wise Interventions to Provide Critical Feedback Across the Racial Divide. American Psychological Association.

Crede, M., Sotola, L.K (2021). Regarding Class Quizzes: a Meta-analytic Synthesis of Studies on the Relationship Between Frequent Low-Stakes Testing and Class Performance. Educational Psychology Review.

Dillinger, K (2023). Surgeon General Lays out Framework to Tackle Loneliness and ‘Mend the Social Fabric of our Nation.’ CNN

Heissel, J.A., Adam, E.K., Doleac, J.L., Figlio, D.N., & Meer, J. (2021). Testing, Stress, and Performance: How Students Respond Physiologically to High-Stakes Testing. Education Finance and Policy, 16(2): 183 – 208.

Hrynowski, Z., Marken, S (2023). College Students Experience High Levels of Worry and Stress. Gallup

Klem, A.M., Connel, J.P. (2004). Relationships Matter: Linking Teacher Support to Student Engagement and Achievement. Journal of School Health, 74(7): 262 – 73.

Peters, S. Toledo, C (2010). Educators’ Perceptions of Uses, Constraints, and Successful Practices of Backchanneling. In Education

Seligman, M. E. (2012). Chapter 1: What is well-being? Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being (pp.5-29). New York: Simon & Schuster.

Slavin, S. J., Schindler, D. L., & Chibnall, J. T. (2014). Medical student mental health 3.0: improving student wellness through curricular changes. Academic Medicine, 89(4), 573-577.

Tyton Partners (2023). Listening to Learners: Increasing Belonging in and Out of the Classroom. https://tytonpartners.com/listening-to-learners-2023-increasing-belonging-in-and-out-of-the-classroom/

Zengaro, S., Zengaro, Z., (2022). Active Learning, Student Engagement, and Motivation: The Importance of Caring Behaviors in Teaching. Handbook of Research on Active Learning and Student Engagement in Higher Education, edited by Jared Keengwe, IGI Global, pp. 66 – 83.